TikTok is the latest social media platform to make its way into our cellphones and our culture, yet its full effects are largely unrealized. Its various impacts span several fields of study; from a psychological standpoint, one might consider what this app does to its users’ minds and relationships with each other. TikTok is ultimately a form of surveillance, alongside Facebook and Instagram and other social media giants. Danish professor Anders Albrechtslund defined surveillance as “the visual practice of a person looking carefully at someone or something from above.”[1] In practice, the term is less literal and can be applied to multiple situations.

When discussing surveillance, one of the best places to turn is the Panopticon. The concept was first introduced by Jeremy Bentham in the late 1800s[2] and has been in and out of discussion for centuries, experiencing a revitalization when French philosopher Michel Foucault wrote about it in 1975[3]. In the years since, scholars have questioned how the Panopticon might function in modern times with modern technology. In this essay, I will discuss TikTok’s relation to Foucault’s concept of the Panopticon as well as a key difference between the two and what the result of that difference has been.

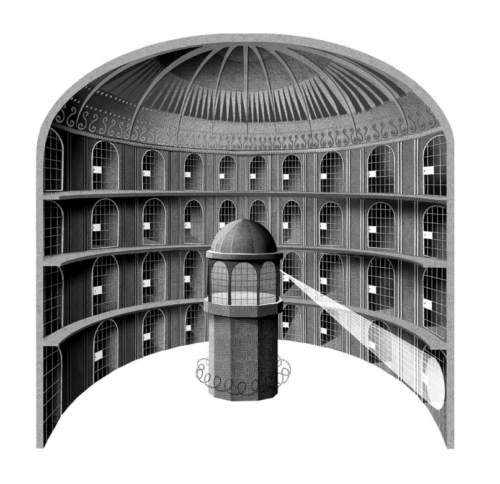

The Panopticon (see fig. 1) had several uses when Bentham proposed it, but it has been most commonly discussed as a prison. By definition, it is a circular building with rooms along the perimeter and a watchtower in the centre. Each room holds a single person. A guard in the watchtower can see the entirety of each room while strategically placed shutters block their visibility, making it impossible to be seen in return[4]. Therefore, any person in any room could be seen at any time by someone in the tower without knowing it. These are the two elements that make up the essence of the Panopticon: first, the ability to be watched and second, the inability to watch in return.

Figure 1: The Panopticon[5]

When Michel Foucault studied these elements, he concluded that they created a power dynamic and affected the prisoners’ behaviour. Historically, behaviour was changed by a hard exertion of power that often came at the expense of the body: chains, locks, bars, and beatings. This is what commonly comes to mind when one thinks of a prison. The Panopticon is different from this precedent because it uses a subtle power that writes itself into every act of the body. Every corner of every room is visible and there is nowhere for the subjects to hide, so they always act as if they are being watched; they become passive under the responsibility of that power, leading to a sense of self-discipline. They act how the observer wants them to act without any interaction between them. According to Foucault, this is the most important effect of the Panopticon: “To induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power.”[6] The subjects are aware in some part of their minds that the guard cannot watch them constantly, but they have no way of knowing where the guard is looking. Thus, they behave as if they are always watched. This makes the guard’s power complete. Ultimately, there is no need for an observer to even be in the tower because the result is the same. They hold a place of authority and maintain power over the subjects at all times.

As for TikTok (see fig. 2), this social media app is centred around short video content. It has risen to popularity in the last few years and it currently hosts over a billion users.[7] Nearly all social media platforms have a section where users can choose to follow content creators and TikTok is no different in that field, but it is unique because of its For You page: an endless stream of videos where anyone’s posts could be viewed. This is what makes the app most appealing; it is especially popular among the younger generations, but people of all ages use it. Most videos on the For You page feature a user visible on screen and speaking on a topic or performing a skill in some way.

Figure 2: TikTok app[8]

At this point, one might wonder how a social media platform has anything to do with a building design from the nineteenth century and its philosophical interpretations. As I previously stated, the first element of the Panopticon is the ability to be watched. When someone makes a video and uploads it to TikTok, that video could then be shown on anyone’s For You page. At any point after a video has been posted, whether it is minutes or months later, someone could watch it. Any of TikTok’s billion users might see the post, which is quite a diverse group of people. If a user’s face is in the video, that face could potentially be seen by thousands of other accounts, behind which are real people with thoughts and opinions on the content.

The second element of the Panopticon is the inability to watch in return. TikTok gives four categories of interaction with any given post: comments, shares, likes, and views. Each comes with a unique amount of visibility. Anyone who sees a post can see other accounts that have commented on it, but only the uploader can see who has shared and liked the post. No one can see who has viewed it. The views are completely anonymous and are also the highest number of the four categories. Therefore, the user cannot know who has watched them. They could be seen at any point in time without knowing who is seeing them. All they receive is a number that tells them the size of their anonymous audience.

These two aspects of TikTok lead to the same result as the Panopticon: “A state of conscious and permanent visibility.”[9] Users’ behaviour is permanently affected by this knowledge. When they post on the app, they know that they could be seen by anyone at any point and they adjust how they act accordingly. There is an awareness embedded in their minds as they film their videos; a small voice that reminds them that people will see them but they cannot decide who and they cannot watch them in return. It might be five or five million but people will see it, and they will continue to see it as long as the video is available.

This is what makes TikTok a type of Panopticon. However, there is a key difference between Foucault’s Panopticon and TikTok: it lies in the power dynamic between the observed and the observer. In the Panopticon, the observer holds a position of authority over the subjects and they act a certain way due to potential negative consequences. Therefore, to be viewed is something that is feared. On TikTok, the observers hold no authority over the user. They are simply an anonymous audience, waiting to see whatever the user offers them. Because of this lack of authority, to be viewed has become something that is desired. TikTok users want to be seen. When they post a video they choose to engage with this audience and be observed by others, even if they cannot observe in return. This is the participatory aspect of TikTok’s relation to the Panopticon: users could be watched by anyone at any time without the ability to watch back, but they choose to engage in it because they benefit from it.[10] They seek the admiration and acknowledgment of others and submit to a certain level of surveillance so that they can obtain it.

This difference is vital. As I have outlined, TikTok meets the criteria to be considered a Panopticon but it is not the same because the viewing is desired rather than feared. This matters because the desire to be viewed has created a gaze within the minds of TikTok users. According to key thinker and philosopher Jacques Lacan, gaze functions out of the unconscious; it is a state of mind that comes with the awareness that one can be seen.[11] Users have this mentality when they use the app. While they create content, they behave a certain way because they know they will be seen. They anticipate the audience they will have and act accordingly, adjusting what they do and say to make themselves appealing to the masses.

This mentality stays with users when they are done using the app, living in their minds as a gaze. After they have stopped recording and put their phone away, they continue to perform for that anonymous audience. It is projected onto strangers that they pass by as they go about the mundanity of their days: buying groceries, sitting in class, walking down the street. An example of this is found in a video made by a TikTok user named Zara, an American woman in her early twenties who posted the video on November 1st, 2021. She was alone and spoke to the camera (see fig. 3), so the subtitles have been transcribed:

I would like to live an unobserved, anonymous, absolutely insignificant, silly little life, but I would like to do it in a way that everybody is looking at me all of the time, and they think, “That is the most beautiful, mysterious, talented, creative, funniest, smartest stranger that I’ve ever seen” (while I’m passing them on the street) and then they think about me every day until they die.[12]

She adds in the caption, “But like in a totally unbothered and aloof way.”[13]

Figure 3: Still from Zara’s TikTok video[14]

Zara’s video had 250,000 views at the time this essay was written, and the comments section was filled with other users agreeing with her. She reveals the gaze that TikTok has given so many of its users. She proves that the desire to be viewed does not stop when the camera is turned off. She and other users want every aspect of their lives, even the simple ones, to be witnessed and admired by the public in the same detached way that the TikTok audience witnesses them. Zara seems to be aware of this phenomenon, but many people are not. They are constantly evaluating themselves through the lens of the anonymous audience without consciously realizing it. They want everyone who sees them to adore them forever afterward without actually engaging with them.

To conclude, TikTok is the participatory Panopticon because users are watched without being able to watch in return, but they choose to engage in this because to be viewed has become desirable. This desire then becomes a gaze that TikTok users internalize. They perform for it whenever they are in public because it is applied to the strangers around them. This proves that TikTok is more than a hub of entertaining videos; it is a mode of surveillance that extracts a certain level of information to be engaged with. This is not to say that the app is necessarily harmful, but it is important to be aware of how it affects its users’ perceptions of themselves and the world around them. This is especially noteworthy when considering the large number of teenagers and young adults that use the app. The upcoming generations have been raised with these social media platforms that amass collections of personal information over time. TikTok is no exception. Every day its users offer themselves up to the watchful eyes of the audience with hardly a second thought. It would be wise for users to fully understand what they are engaging in before they step into the participatory Panopticon so that when they step out, they can leave the anonymous audience behind.

[1] Anders Albrechtslund, “Online Social Networking as Participatory Surveillance,” First Monday 13, no. 3 (2008): 6.

[2] Jacques-Alain Miller and Richard Miller, “Jeremy Bentham’s Panoptic Device,” October 41 (1987): 3.

[3] Michel Foucault, “Panopticism,” in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Random House, 1995), 200.

[4] Miller, “Jeremy Bentham’s Panoptic Device,” 4.

[5] Adam Simpson, “The Panopticon,” Digital Image, adsimpson.com, 2013.

[6] Foucault, “Panopticism,” 201.

[7] Jessica Bursztynsky, “TikTok says 1 billion people use the app each month,” cnbc.com, CNBC, September 27th, 2021.

[8] Xinhua/Shutterstock, “TikTok app on iPhone,” Digital Image, theguardian.com, 2021.

[9] Foucault, “Panopticism,” 201.

[10] The benefits were not relevant enough to describe in detail but the biggest one is going viral and gaining the resulting opportunities.

[11] Jacques Lacan, “The split between the eye and the gaze,” in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis, trans. Alan Sheridan, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller (New York: Norton, 1977), 43.

[12] Zara (@cowbabyzee), “I would like to live an unobserved, anonymous, absolutely insignificant, silly little life…,” TikTok, video, November 1st, 2021, https://www.TikTok.com/@cowbabyzee/video/7025736996018490630

[13] Zara.

[14] Zara.