When considering the Baroque period of European history, piracy is one of many aspects that made it unique: international waters were flooded with pirates during this time. In this paper, I am looking at three pirate ships that sailed between 1680 and 1730: Blackbeard’s Queen Anne’s Revenge, William Dampier’s Batchelor’s Delight and Bartholomew Roberts’ Royal Fortune. I argue that the adaptations that these pirates made for strength, speed and stealth respectively turned their ships into unique machines for private enterprise that caused friction in maritime trade. Blackbeard put additional cannons on his gun decks so that he could pose a larger threat when attacking his targets. Dampier levelled his decks and cleaned his ship’s hull so that it would sail faster and allow him to both escape from and chase after other ships. Roberts collected European countries’ flags and flew them falsely, allowing him to sail past uninterrupted or get close before revealing his true pirate colours. These adaptations illustrate how pirates operated independently and increased friction in trade routes since the European nations that were already in competition were forced to reckon with pirates as well.

To fully understand how piracy impacted maritime trade, one must first understand how trade functioned at the time. Coastal shipping routes around European countries were long established when in the sixteenth century, ships sailed out farther in pursuit of the supposed New World and crossed oceans to places like the Caribbean. There were valuable goods there and merchants began establishing trade routes to bring them back to Europe.[1] This involved setting up colonies and systems of collecting goods so that they were prepared when the ships arrived. Similarly, merchants designed systems in their home countries that processed and distributed the goods they acquired. These goods strengthened the countries that they were brought back to, increasing competition between major players such as Spain, England, France, Denmark, and Portugal. These countries had existing rivalries that varied in intensity throughout time, but an increase in power across the ocean meant an increase in power next door and the ability to pose greater threats. Thus, rivalries extended into the water.

The perspectives at the time were that acquiring commodities not only meant a country’s gain, it also meant other countries’ loss.[2] This furthered division and in times of higher conflict, some countries would hire privateers to steal from competitors. Sir Francis Drake, for example, was hired by Queen Elizabeth the First of England to raid Spanish ships and colonies in the late sixteenth century.[3] This competition also meant that merchants were armed and sailed in small ships, which were preferred because they carried less cargo so there was less risk if they were lost.[4] The open water was an unpredictable and dangerous place, and European merchants responded as best they could. Networks strengthened and navigation improved throughout the sixteenth century but many dangers remained, including the danger of piracy.

Piracy, by definition, is “larceny at or by descent from the sea.”[5] This definition is important because it includes larceny (theft) that happened adjacent to but not in the open water. The common consideration of pirates is men on ships attacking other ships, but they relied on land sources as well as maritime ones. These land sources were largely in the Caribbean and other colonies that European countries had established throughout the previous two centuries. Despite this history, these colonies were not closely managed because imperial powers were focused within Europe: numerous wars occurred in Europe at the end of the seventeenth century.[6] These left vulnerabilities that pirates took advantage of in a period known as the Golden Age of Piracy that spanned from approximately 1680 to 1730. This period was also made possible because nearly all pirates were sailors and seafarers for European countries during these wars and when they ended, many chose to defect and turn to piracy rather than leave their lives on the sea.[7] This existing naval education was vital for the success of piracy. Though they did not build their own, pirates were trained to work with and understand ships; they knew quality when they saw it, and they were selective with what they sailed.

William Snelgrave, an English slave trader, testified to this selectiveness. When his ship was captured and boarded by pirates in 1719, they asked him about how his ship sailed. He replied that it sailed “very well” and the pirates declared that it “would make a fine Pirate Man of War.”[8] There were numerous ship typologies that sailed during this time, largely split into merchant ships and warships, but not all of them made a good pirate ship. Merchant ships were small and built to balance speed, carrying capacity, and cost.[9] When they were operated as slaving ships, their crews temporarily adapted them to hold enslaved people: for most of their time at sea, they appeared and operated as any other merchant ship would.[10] War ships, on the other hand, were bigger, slower, and filled with cannons.

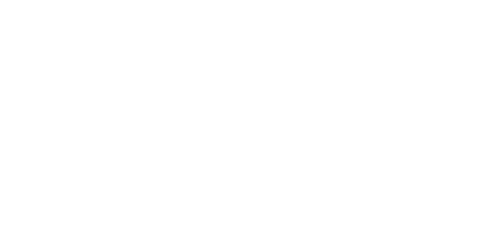

Figure 1 shows illustrations of two English warships from Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopaedia. The illustrations show the large number of cannons, as well as their organization: larger ones on lower decks and smaller ones up higher so that the ship did not become top-heavy. While merchant ships were also armed, this abundance of cannons was one of the main differences between ship typologies, as their sails and rigging varied little from each other.[11] These differences in type mattered to pirates. Since they did not build their own ships, the ships that they acquired had to suit their criteria. However, pirates had different intentions from European sailors and thus they sought ships that made good bases for the adaptations they made to suit their unique purposes. Most of the ships they ended up with were merchant ships, although it was not unheard of for a warship to find a place in a pirate fleet.

Figure 1. Labelled illustrations of two English warships. The bottom one was a larger type that was more armed than the smaller one depicted above it.[12]

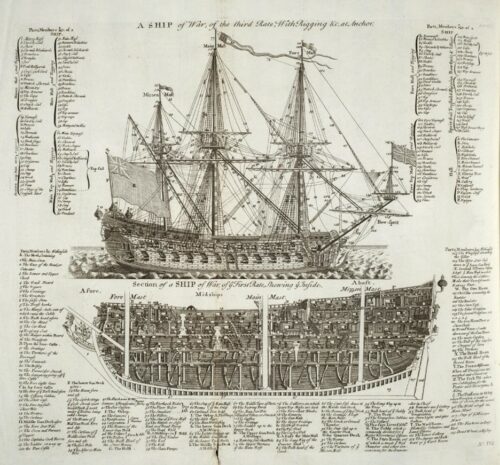

The first of the adaptations that this paper examines is the addition of cannons for strength. Pirates used their cannons to defeat other ships, but not always in the obvious ways. Their goal was not to sink or destroy opposing ships: if it was a suitable ship, they would want it for their fleet and if not, they could at least steal its cargo. Thus, cannons were used to threaten as much as they were to attack. One of the best examples of this is Captain Edward Thatch, better known as Blackbeard, and his ship Queen Anne’s Revenge. This ship was a large French slaving ship named La Concorde that Blackbeard captured in the Caribbean in 1717. He took the ship but left most of the enslaved people to the French, along with one of his ships so they could continue their transport. Queen Anne’s Revenge became his flagship and as he plundered more ships from whatever European merchants had the misfortune of running across him, he moved their cannons to Queen Anne’s Revenge until it held forty: more than double what it started with.[13] The wreck of Queen Anne’s Revenge has been excavated and cannons of various sizes and designs have been found (figure 2), supporting the concept that Blackbeard collected them from different country’s ships.

Since La Concorde was a merchant ship, this number of cannons was unusual. They would have required additional infrastructure in the gun decks, crew to man and maintain them, and they added tonnes of weight to the ship which slowed it down. However, it was a worthwhile endeavour for Blackbeard. He took Queen Anne’s Revenge for the speed and carrying capacity it had as a merchant ship, but the additional cannons posed more of a threat. He sailed around in a ship that was outfitted with mismatched cannons from his previous victims, many of which documented their encounters.[14] The ship added to his reputation and allowed him to take down other vessels, when necessary, but he often found success from warning shots alone. His adaptations to Queen Anne’s Revenge made it uniquely strong for a merchant ship, and this allowed him to add friction to trade routes by threatening both ships and ports.[15]

Figure 2. Cannons recovered from Queen Anne’s Revenge wreck.[16]

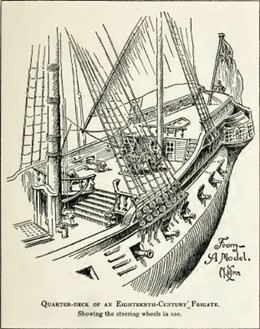

The second of the adaptations that pirates made was for speed. According to Charles Johnson, author of A General History of Pyrates, a fast ship “was of great use either to take or to escape being taken” at sea.[17] Speed was the lifeblood of piracy and one of the ways pirates adapted for it was by ditching cargo and breaking down parts of their ships. When faced with the choice between losing some goods or losing to an attacking ship, pirates chose mobility and threw barrels and boxes overboard. They also removed interior partitions and levelled the decks of ships they acquired, rearranging them and lightening them significantly.[18] William Dampier, a pirate who sailed Batchelor’s Delight in 1685, records this practice, writing that he and his crew “cut down our quarter-deck to make the ship snug, and the fitter for sailing.”[19] Figure 3 shows what the quarter deck of a ship looked like during this period: it was no small element of the ship. This process of adaptation required a deep understanding of ship construction and the skills to see it through.

Figure 3. Illustration of an eighteenth-century frigate. Using the doors for scale, it is clear that this section of the ship was large enough to hold rooms.[20]

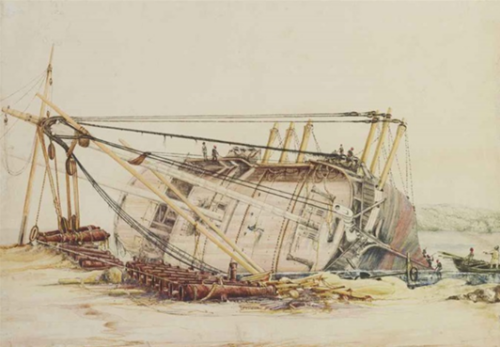

Another way pirates adapted their ships for speed was through a process called careening. Careening involved hauling a ship onto the beach and scrubbing the barnacles off the hull, as this buildup could significantly slow it down.[21] Dampier also recorded this in his journal, explaining that it was done so “that we might be ready to intercept this fleet.”[22] Careening was especially dangerous for pirates, as they essentially stranded themselves while performing the exhausting task. Edward Cooke’s illustration of this process (figure 4) shows how a ship’s contents had to be removed so that it could be tilted, which meant additional labour and time. However, men like Dampier knew how much of a difference careening could make. William Hasty, a geographer at the University of Glasgow, writes that “the ship and its constituent parts were never sacred in the hands of pirates. The ship was their home at sea, but it was also a tool for transport, one that had to be honed for the purpose of the pirate through modification.”[23] Dampier worked to keep this tool in its best condition. Every ship that was out in the ocean needed to be careened regularly, but merchants and navies rarely afforded the time for it. Their employers even banned the practice at times because they wanted to spend the money elsewhere.[24] This difference in priorities is evidence of how pirates used their ships for private enterprise which was unique from European practice and actively caused trouble in it. Pirates like Dampier could either catch up to or get away from a European ship, whichever best served their interests at the time, and the ship was too slow to do anything about it.

Figure 4. Illustration of a careened ship. The cannons are set to the side and sailors are visible on the hull.[25]

The last adaptation that this paper examines was one that pirates did for stealth: flying false flags and pirate flags. Ships were required to fly national flags, so pirates collected the flags of major European countries from ships they plundered and raised them so that they could sail past other ships with no suspicion.[26] This also worked when they wanted to sneak up on targets. Once they were close enough, the pirates made themselves known by raising a black flag with imagery of death: the Jolly Roger. This flag was a signal that meant, according to historian Peter Leeson, “If you resist us, we’ll slaughter you. If you submit to us peacefully, we’ll let you live.”[27] The flag took multiple forms throughout its use before the skull and crossbones were widely accepted. Captain Bartholomew Roberts designed a personalized Jolly Roger that depicted him shaking hands with death. Charles Johnson included this flag flying from Roberts’ ship, Royal Fortune, in his book about Golden Age pirates (figure 5).

While this adaptation was one of the least labour-intensive ones that pirates made, it was incredibly effective. Like Blackbeard’s cannons, Roberts’ flags threatened his targets into surrendering without even attempting to fight. Pirates made it clear that they did not abide by the codes that merchants and navies operated on, and they could not be held back by the law: they were a force unto themselves, and their flags communicated that.[28] It did not matter how important a merchant’s cargo was or how big their ship might have been, the pirates would bring destruction and death unless they were met with cooperation. Their flags enabled this reputation and helped pirates disrupt maritime trade, as they could essentially steal from any ship and merchants knew it.

Figure 5: Captain Bartholomew Roberts with his ships, flying pirate flags. The flag that features himself and Death is pictured on the closest ship to the front.[29]

Pirate flags, false flags, clean hulls, level decks, and extra cannons: these adaptations allowed Captains Roberts, Dampier, and Blackbeard to transform their vessels from merchant ships to pirate ships. In the Baroque period, sailors were spending more time on ships than ever before and these complex, mutable spaces were shaped to serve the needs of their users. Pirates took the ships they found and crafted them into their own worlds. They worked in a period of unique opportunities, growing within gaps and establishing their own systems that leached off European maritime trade routes. While European powers focused on power expansion and accumulating more wealth than their neighbours, pirates focused on personal gain directly from European trade. They became so effective at this that the only way to stop them was to acknowledge the severity of piracy and actively work to stop it.

After years of merchants losing their ships, risking their lives, and being forced to adapt by taking smaller loads and travelling in groups, European rulers could not deny how much piracy was interrupting their worldmaking efforts. Through the consistent and expansive development of laws and initiatives, the Golden Age of Piracy eventually came to an end.[30] The dynamic environment of pirate ships ended with it, but their adaptations serve as evidence of how much more complicated the world was in the Baroque period than it might look at first glance. The built environment of the Baroque is partially defined by massiveness and ornamentation, but pirate ships were extremely purpose-driven: anything that was not considered necessary was tossed overboard. These ships affected their surroundings with both their form and their purpose. European countries faced many challenges in their expansion and growth throughout the world and these challenges were directly reflected in the menacing, makeshift forms of ships that were shaped by people who did not care about claiming land or dying for their country. They subverted their political environment by subverting ships they acquired, thus complicating the European domination that was being accomplished through maritime trade.

[1] Oliver Dunn, “A Sea of Troubles? Journey Times and Coastal Shipping Routes in Seventeenth-Century England and Wales,” Journal of Transport History 41, no. 2 (2020): 184.

[2] Phillip Reid, “Something Ventured: Dangers and Risk Mitigation for the Ordinary British Atlantic Merchant Ship, 1600–1800,” The Journal of Transport History 38, no. 2 (2017): 196.

[3] Kris Lane, “Pirate Networks in the Caribbean,” in Empires of the Sea: Maritime Power Networks in World History, edited by Rolf Strootman, Floris van den Eijnde, and Roy van Wijk (Brill, 2020): 340.

[4] Reid, “Something Ventured,” 199.

[5] Lane, “Pirate Networks,” 340.

[6] C. Paul Hallwood and Thomas J. Miceli, “Piracy in the Golden Age, 1690–1730: Lessons for Today,” in Maritime Piracy and Its Control: An Economic Analysis (New York: Palgrave Pivot, 2015): 98.

[7] Hallwood, “Piracy in the Golden Age,” 98.

[8] William Snelgrave, A New Account of Guinea, and the Slave Trade (London: J. Wren, 1754): 213.

[9] Reid, “Something Ventured,” 200.

[10] Jane Webster, “Slave Ships and Maritime Archaeology: An Overview,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 12, no. 1 (2008): 7.

[11] Nick Burningham and Phillip Reid, “Revisiting the Brigantine Problem: The Origins and Development of Eighteenth-Century Two-Masted Square-Rigged Ship Types,” Mariner’s Mirror 108, no. 4 (2022): 417.

[12] “A Ship of War,” 1728, in Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia (London: 1728).

[13] David D. Moore, “Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard,” The North Carolina Historical Review 95, no. 2 (2018): 163-64.

[14] Moore, “Captain Edward Thatch,” 166.

[15] Moore, “Captain Edward Thatch,” 172.

[16] David D. Moore, Cannon Assemblage from 31C314, 2001, illustration, JSTOR.

[17] Charles Johnson, A General History of the Pyrates (London: T. Warner, 1724): 168.

[18] Hasty, “Metamorphosis Afloat,” 359.

[19] William, Dampier, A New Voyage Around the World (London: J. Knapton, 1699): 380.

[20] Quarter Deck of an Eighteenth-Century Frigate, 1913, illustration, Public Domain.

[21] William Hasty, “Metamorphosis Afloat: Pirate Ships, Politics and Process, c. 1680-1730,” Mobilities 9, no. 3 (2014): 357.

[22] Dampier, A New Voyage, 171.

[23] Hasty, “Metamorphosis Afloat,” 357.

[24] Hasty, 357.

[25] Edward Cooke, An Armed Vessel Careened on the Beach, 1800s, illustration, Artnet.

[26] Hasty, “Metamorphosis Afloat,” 357.

[27] Peter T. Leeson, “Skull & Bones: The Economics of the Jolly Rogers.” In The Invisible Hook: The Hidden Economics of Pirates (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009): 99.

[28] Leeson, “Skull and Bones,” 99.

[29] “Bartholomew Roberts,” 1724, in Charles Johnson, A General History of the Pyrates (London: T. Warner, 1724).

[30] Lane, “Pirate Networks,” 57.