A trip to the spa might be considered a modern luxury, but wellness centres have been part of human health for thousands of years. The largest Roman imperial baths in history, the Baths of Diocletian, opened in 306 AD after eight years of construction. Commissioned by Maximian in honour of his co-emperor Diocletian, the baths were situated on the northeastern edge of the city and served the Roman people until the city was besieged in 537 AD.[1] Groupe Nordik’s third Canadian wellness centre, Thermea Spa Village, opened in early October 2022. The village is in the town of Whitby, which is approximately an hour northeast of downtown Toronto by car and two hours by public transit.[2]

These two wellness centres can be considered through the lens of their places in history and how their designs function within these settings. They were selected for comparison because they are both proximal to major cities and primarily serve the residents of those cities yet are separated by nearly two thousand years of history and look incredibly different from each other. Whereas the Baths of Diocletian were organized into a palatial central building with a secondary ring around it, Thermea Spa Village is organized into a collection of small, rustic buildings. Despite these unique organizational and design styles, the two centres achieve three aspects of wellness in similar ways: social wellness, by encouraging interaction between visitors; physical wellness, by providing amenities that promote bodily healing; and mental wellness, by creating an escape and a place of rest.

Figure 1: Floor Plan of the Baths of Diocletian[3]

The first aspect of wellness that the baths and the village accomplish is social wellness. The baths were accessible to the entire community and once visitors arrived, they mixed with each other because the bath services were all housed in the central building (see fig. 1). This is discussed by Stephen Verderber in Innovations in Hospital Architecture, where he writes, “Built as civic monuments, public baths were used by everyone, rich or poor, free or slave.”[4] The baths reflected the emperor’s power and were thus grand and palatial in style. This design brought the community together because each visitor was able to partake in an aspect of royalty, no matter who they were. This shared positivity fostered social wellness because it gave visitors the opportunity to spend time with their family, friends, and other members of the community.

Figure 2: Thermea Spa Village’s El Resto[5]

Similarly, although Thermea Spa Village has a sprawling organisation, it also has key places where socializing is encouraged: on the website, each of the three restaurants highlight socializing in their descriptions. One reads, “Everything here is just right, … most importantly, the people,”[6] while another boasts, “You’re enveloped by the buzz of social energy,”[7] and the third claims, “There’s something communal about sharing food.”[8] These social spaces are designed within the theme of natural, historic architecture. The seating is casual (see fig. 2) so that interaction is easy between those who visit together or between strangers—everyone can share in the social aspect because the room is filled with the sounds and sights of others having the same experience. The restaurants are all situated next to each other (see fig. 3), creating a social hub within the village and an easy destination for visitors to seek out social wellness.

Figure 3: Site Map of Thermea Spa Village[9]

The second aspect of wellness that the baths and the village accomplish is physical wellness. The village has organised its buildings to create the ideal path along the thermal cycle (see fig. 3), which the website describes as “an alternation between hot and cold, followed by rest. Better sleep, improved physical and mental health, accelerated recovery and healing are only a few of the benefits.”[10] Each of the buildings that house these amenities is thoughtfully designed using wood and stone, creating an atmosphere that feels both ancient and familiar and is ultimately comfortable to be in. Each phase of the cycle is marked by a change from one building to another, which helps distinguish each new experience. The thermal cycle is the village’s main contribution to physical wellness and the design and organization make this successful.

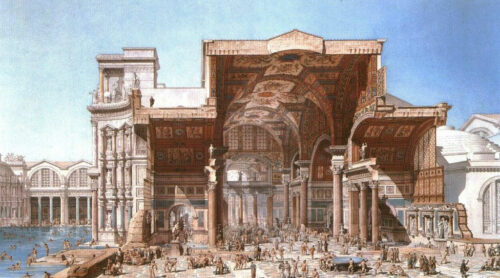

Figure 4: Cross-section of the Baths of Diocletian[11]

The baths followed a similar cycle within the central building, with different sections housing different steps in the routine. The Romans considered this a “a vital part of any health regimen”[12] as it was how they maintained good hygiene and prevented disease. Because the cycle was centralized, visitors were enveloped in the grand, palatial architecture the entire time they attended the baths. This organization also made it easier to keep the baths clean and functional; both the water and the building were heated and cooled through a series of subfloor systems, so any additional distance would have required more technology and effort. The baths’ scale also made it possible for large groups to use them at one time without overcrowding (see fig. 4), which would have detracted from the health benefits.

The third aspect of wellness that the baths and the village accomplish is mental wellness. In Evans and McCoy’s When Buildings Don’t Work, they highlight the importance of choice in this context: “Physical constraints that reduce choice or behavioural options can produce or exacerbate stress.”[13] People want to have control and make decisions about where they go and what they do. This freedom is key in relieving mental fatigue. Additionally, according to Kaplan’s Attention Restoration Theory (ART), an escape alone cannot provide mental restoration—there must also be a connection to nature.[14] These concepts are reflected in both the baths and the village.

At the baths, the first stage of control is a visitor deciding to leave their humble home and go to the opulent baths, while the second is choosing what they do there. The baths “provided something for everybody”[15] and this variety of options created a feeling of empowerment. The restorative experience was completed by the baths’ open spaces, fresh water and green space between the baths and the outer ring of amenities (see fig. 5). This design created an escape that felt separate from the city and gave visitors agency while they rested.

Figure 5: Model Reconstruction of the Baths of Diocletian[16]

Likewise, the village promotes itself as “A neighbouring village for you to escape to … and leave your worries behind.”[17] Residents of the cities around it can choose to go to a historic, small-scale oasis that is a change from their usual spaces. This departure from the mundane adds to the feeling of escape. Like the baths, the second layer of choice is provided through the variety of options and ways to spend one’s time, but unlike the baths, the small village structures use simple, natural materials. They too are surrounded by fresh air, water and greenery (see fig. 6). This creates a sense of peace and mental rest so that visitors can reset and enjoy the social and physical aspects of wellness even more.

Figure 6: Two of Thermea Spa Village’s Sauna Buildings[18]

In conclusion, both the Baths of Diocletian and Thermea Spa Village are successful at achieving three aspects of wellness despite their vastly different design and organisational styles. They achieve social wellness by promoting group activity and interaction within their spaces: the baths put everyone in one building and promoted accessibility, while the village has designated rest areas and restaurants at various locations. They achieve physical wellness through their thermal cycle systems and other amenities: the baths used a centralized organization that made maintenance efficient, but the village separates each phase into a building and organises them along a path. They achieve mental wellness by providing choices and restoration: the baths held various amenities in a setting that was both opulent and natural, while the village is a smaller scale than the city that is filled with natural, timeless elements.

These two wellness centres achieve wellness because their design and organisation respond to their audiences. A palatial structure was successful for the Romans because they could be immersed in grandeur even while remaining in the city, but in Toronto this style would be yet another large building. On the other hand, the village is suited to modern city dwellers because they are accustomed to grandness so a small scale, historic collection of buildings that evokes a timeless past is the escape that they need. This proves that when designing a wellness centre, or any building for health, it is vital to be aware of its setting and its visitors’ needs so that the centre can most successfully support them.

[1] Samuel Ball Platner, “Thermae Diocletiani,” In A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, (London: Oxford University Press, 1929), 527.

[2] Group Nordik, “About Us,” Thermea Spa Village Whitby, 2022, https://www.thermea.com/about-us

[3] Banister Fletcher, Baths of Diocletian Plan, Digital Image, JSTOR, 1921, https://jstor.org/stable/community.12091699

[4] Stephen Verderber, “Architecture for Health: A Brief History of Sustainability,” In Innovations in Hospital Architecture, (London: Routledge, 2010), 14.

[5] Groupe Nordik, El Resto, Digital Image, Thermea Spa Village Whitby, October, 2022, https://thermea.com/whitby/restaurants

[6] Group Nordik, “Restaurants,” Thermea Spa Village Whitby, 2022, https://thermea.com/whitby/restaurants

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Groupe Nordik, Site Map, Digital Image, Thermea Spa Village Whitby, October, 2022, https://thermea.com/whitby/thermal-experience/spa-village

[10] Groupe Nordik, “The Experience,” Thermea Spa Village Whitby, 2022, https://thermea.com/whitby/thermal-experience/experience

[11] Edmond Paulin, Cross-section of the Baths of Diocletian, Digital Image, ThermoTherapyNow, 1880, https://thermotherapynow.org/wp/thermotherapy-through-history/

[12] Judith Testa, “The Baths of Caracalla and of Diocletian,” In Rome Is Love Spelled Backward: Enjoying Art and Architecture in the Eternal City, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998), 52.

[13] Gary W. Evans and Janetta Mitchell McCoy, “When Buildings Don’t Work: The Role of Architecture in Human Health,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 18, no. 3 (1998), 91.

[14] Rachel Kaplan and Stephen Kaplan, “The Restorative Environment,” In The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1989.

[15] Testa, “The Baths,” 55.

[16] Andre Caron, The Baths of Diocletian, Digital Image, Maquettes Historiques, 1995, https://www.maquettes-historiques.net/P23.html

[17] Groupe Nordik, “The Spa Village,” Thermea Spa Village Whitby, 2022, https://thermea.com/whitby/thermal-experience/spa-village

[18] Groupe Nordik, View of the Saunas, Digital Image, Thermea Spa Village Whitby, 2022, https://thermea.com/whitby/thermal-experience/spa-village