Lina Bo Bardi was an Italian immigrant who moved to Brazil in 1946 after she married Pietro Maria Bardi, a respected art historian.[1] While she is best known for her modernist architecture, Bo Bardi also worked as a curator, writer, furniture designer, preservationist and political activist.[2] Her relationship with modernism was unique: she was definitely a modernist in terms of style and values, but she did not fit in with the other modernist architects in Brazil because she refused to ignore Brazilian culture and identity. The latter half of her life became defined by her connection to Brazil and its traditional, regional culture. This culture became an intrinsic part of Bo Bardi’s work throughout the rest of her career, in architecture projects and other ventures.

The world after the war was one focused on progress, on the bright hope of a new tomorrow, and traditional cultures like the one found in Brazil were often described as folklore. In the Cambridge Dictionary, folklore is defined as “the traditional culture of a group of people”[3] but in the mouths of modernists, it was a negative term used to invalidate the Brazilian people and their work. It made their traditions appear to belong only in the past and have no place in modern society. Bo Bardi disagreed with these judgements. Her appreciation of the vernacular culture of Brazil increased with every day that passed. Five years after she moved to Brazil, she designed her home (figure 1) in the middle of the rainforest on the outskirts of São Paulo.[4]

Figure 1. Lina Bo Bardi in her home, Casa de Vidro (Glass House).[5]

It was a shining example of modernism yet it was filled with traditional objects she had collected. Lina Bo Bardi’s methods of representing Brazilian culture in her work reveal what she believed about folklore: that it is a valid part of modern society, that it reveals the truest aspects of humanity, and that it is no less important than other values. These beliefs were reflected in the projects she completed both as a curator and as an architect.

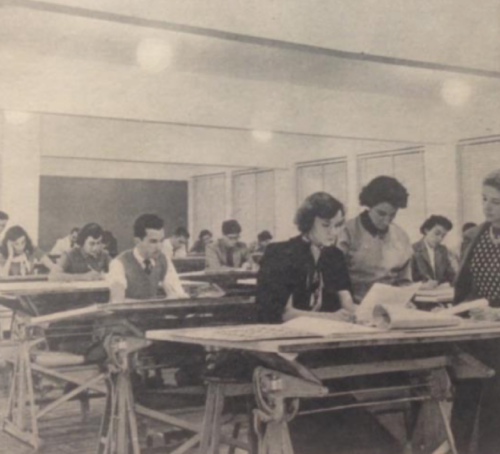

One of the notable aspects of Lina Bo Bardi’s early career in Brazil was her role in creating the Institute of Contemporary Art (IAC). Modern architecture was introduced to Brazil in the 1930s, so it had already been part of society for over ten years by the time Bo Bardi moved there.[6] As a modernist herself, it would have been easy for Bo Bardi to ignore the regional architecture like many others had. However, she saw the value in the traditional Brazilian styles and the local people who had created them. That is why Bo Bardi and her husband opened the IAC in 1951 and worked as professors at the school.

Figure 2. Students at the IAC.[7]

Bardi wrote the following about the design school: “The Institute of Contemporary Art is an initiative of São Paulo’s Art Museum. Its purpose is to boost research in the field of the applied arts. Its approach will be distinctly contemporary. It will provide guidance for industrialists, so that household objects in common use may reach a higher aesthetic level in tune with the current period.”[8] This school was meant to invest in local Brazilian talent and cultivate a generation of modern artists and designers who knew Brazil.

Figure 3. Students participate in a model workshop at the IAC.[9]

The school was scholarship-based so that local, lower-class citizens could attend, and the program was tied to Brazil’s cultural roots. Bo Bardi wanted to bring the local culture into modern society and the contemporary art world. She believed that folklore and modernism could not only coexist but meld into something better than either was on its own. However, the school did not last and was closed by the end of 1953.[10] Alexandre Wollner, a member of the first class of the IAC, said the following when discussing the school: “Industry showed no interest in tapping the talents of the newly graduated designers. Most Brazilian industrialists preferred to pay royalties for making products here, or to import items manufactured abroad (often not suited to our culture and technology) instead of investing to develop them locally. This has been going on for fifty years and continues to this day!”[11]

Brazilian industrialists were importing products from other countries and shoehorning them into Brazilian society, but Wallner recognized that the products did not fit. Bo Bardi saw this too. She did not view folklore and traditional culture as something to be left in the past; she believed that Brazil would benefit the most from having production and design come from within because it would be informed by real Brazilian experience and the locals would know better what could function well in Brazil.

Lina Bo Bardi’s connection to Brazil began as soon as she stepped foot in it, but it reached its deepest point after she began to work in Bahia. The northeastern region boasts an even richer traditional culture than the major cities of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, and Bo Bardi was quickly entranced by it. She spent a great portion of her career there, working on projects that celebrated the local culture and people. In 1959, Bo Bardi worked alongside Martim Gonçalves and an exhibition titled Exposição Bahia (Bahia Exhibition) was held for the fifth biennial in São Paulo (figure 4).

Figure 4. View of the Bahia Exhibition.[12]

In the introduction for the exhibition, Bo Bardi wrote, “It is in the sense of being entirely connected to life that we present this exhibition. It is a way of being that extends to the way of looking at things, of moving, of placing one’s feet, a way that is not “aesthetic” but is close to nature, to the “true” human being … We present Bahia … where what is known as “culture” has not yet arrived.”[13] Lina Bo Bardi was not so easily swept away by the modern thinkers of her time. She believed the traditional practices of Brazilian folklore were much more deeply connected to life than any modern metal fabrication could hope to be. Bahia was a region known for its high rates of poverty, and the exhibited objects were scraped together with whatever the locals could find. Bo Bardi did not shy away from this; she recognized that this was a culture just as legitimate as Western culture.

Four years later, she did a second exhibition in Salvador, Bahia titled Nordeste (North East) (figure 5). When introducing this exhibition, Bo Bardi wrote, “We call this a Popular Art Museum rather than a Folklore Museum, because folklore is a static and regressive term, which is sustained by those responsible for culture; whereas popular art (and we use the word “art” not just in the sense of the fine arts, but also in the sense of making something technically) defines the progressive attitude of popular culture connected with real problems.”[14]

Figure 5. Display of artifacts at the Nordeste Exhibition.[15]

This exhibition presented ordinary objects from Bahia in defiance of the modern ideals of aesthetics and definitions of civilization. Bo Bardi knew how the term ‘folklore’ had been used to condemn Bahian culture so she addressed this in her exhibition. Both of these exhibitions were defiant reminders that Bo Bardi had embraced the Brazilian folklore and believed that it was a close depiction of humanity in the face of increasingly distanced modernism. Following her time in Bahia, Lina Bo Bardi designed the Museum of Art of São Paulo (MASP) and it was completed in 1968.[16] The display that she organized defied all the Western methods of presentation. The open space of the gallery was filled with paintings that were attached to individual panels of glass with concrete cubes as bases (figure 6).

Figure 6. Bo Bardi’s display at the MASP.[17]

This made the paintings appear to float at eye level. This directly contrasted the typical white wall style that Western museums had deemed the correct way to display art. In his article “This Exhibition Is an Accusation: The Grammar of Display According to Lina Bo Bardi”, Roger M. Buergel wrote, “Presenting classical Western painting in such a spectacular display as a total image in and of itself—an image of artistic labour—put an end to all received wisdoms of systematicity (be they chronology, genre, styles, -isms, international school). It laid any universal claim about the Western idea of art to rest.”[18] Organization creates a path for viewers to follow, leading them through the work and depositing them nicely on the other side—Bo Bardi’s display was different. By removing organization, she removed any sense of hierarchy or direction and forced the viewer to create their own path and be faced with every painting at once.

Bo Bardi was impacted by the traditional culture that she experienced in Bahia; a culture that was more personal and focused on the individual instead of engineered systems. She maintained that her method of organization was no less valid than the Western white wall method or any other method that curators had designed. Each had its benefits and disadvantages, but none was inherently superior to the other. Just like how the people of Bahia and their traditions were no less valuable than the West and its shiny new inventions. After Bo Bardi’s death, the display she created was taken down and turned into the typical white wall system of organization.[19] However, in 2015 the MASP brought back her method of display (figure 7).

Figure 7. The MASP’s recreation of Bo Bardi’s display.[20]

Lina Bo Bardi was a notable architect because of her attention to the region. She fell so in love with the Brazilian culture that she became one of its loudest advocates. She embraced what others ignored or tried to cover up with promises of a new Brazil—history, poverty, vernacular, tradition, folklore. She founded the Institute of Contemporary Art so that local artists who were familiar with traditional styles could contribute to Brazil’s growth. She did this because she believed that folklore does not belong in the past; it is a functional and valid part of modern society. She put on two notable exhibitions in Bahia because she believed folklore was a far truer representation of humanity than modern designs which were created solely to be efficient and aesthetically pleasing. She designed the Museo de São Paulo and created a display without systems of organization; one where every painting was equal to its neighbour. She created a new method of display that was inspired by the folklore she had seen in Bahia, by the wealth of value she had found in these people that everyone else had filed away into the past. She used her work to assert her belief that folklore was no less valid than other cultures and values.

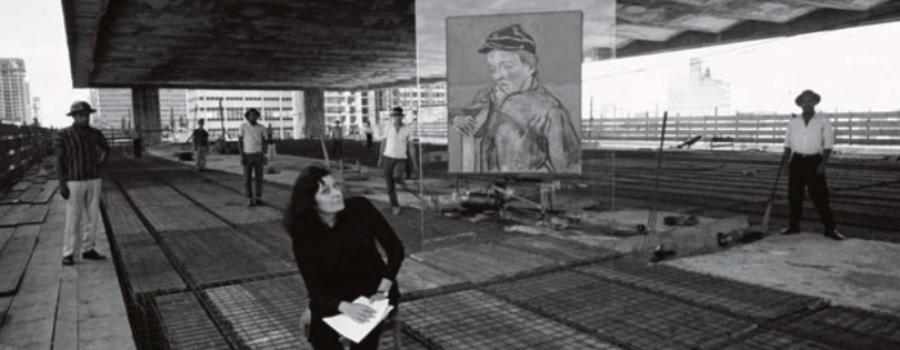

Figure 8. Bo Bardi at the construction of the MASP.[21]

Her career is defined by these projects that are not high in number but are each unique and informed by the local culture. Lina Bo Bardi was never one to shy away from speaking her mind and advocating for her beliefs, even before she moved to Brazil; but when she did—when she became involved with Brazilian folklore—she realized that a building is defined by the people within it. With this in mind, she went on to design the projects that earned her a well-deserved title: ‘architect of the people’.[22]

[1] Sources were found by searching “Lina Bo Bardi” in both the University of Toronto Libraries database and jstor.org. The filters that were used were language (English) and content (Architecture and Architectural History), then the results were sorted by relevance.

[2] Steffen Lehmann, “An environmental and social approach in the modern architecture of Brazil: The work of Lina Bo Bardi” in City, Culture and Society (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2016), 182.

[3] Cambridge Dictionary, (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), s.v. “Folklore,” https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/folklore

[4] Lina Bo Bardi, “Three Essays on Design and the Folk Arts of Brazil” in West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture, Vol. 20, No. 1, trans. Zanna Gilbert, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Spring-Summer 2013), pp. 110-124.

[5] Francisco Albuquerque, 1952, photograph, Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi, São Paulo.

[6] Lehmann, “The work of Lina Bo Bardi,” 182.

[7] Assis Chateaubriand, 1952, photograph, Library and Documentation Center of the São Paulo Art Museum, São Paulo.

[8] Pietro Maria Bardi, A Cultura Nacional e a Presença do Masp (São Paulo: Fiat do Brasil).

[9] Peter Scheier, 1951, photograph, Library and Documentation Center of the São Paulo Art Museum, São Paulo.

[10] Ethel Leon, “The Instituto de Arte Contemprañea: The First Brazilian Design School, 1951–53” in Design Issues, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2011), pp. 111-124.

[11] Alexandre Wollner interview conducted on June 23, 2004.

[12] Miroslav Javurek, 1959, photograph, Instituto Lina Bo e P. M. Bardi, São Paulo.

[13] Lina Bo Bardi, “Three Essays”, 120.

[14] Bo Bardi, 123.

[15] A. Guthmann, 1963, photograph, Instituto Lina Bo e P. M. Bardi, São Paulo.

[16] Lina Bo Bardi, “Museo De Arte De São Paulo.” in ANY: Architecture New York, no. 5 (New York: Anyone Corporation, 1994): 24-25.

[17] Paolo Gasparini, 1968, photograph, Instituto Lina Bo e P. M. Bardi, São Paulo.

[18] Roger M. Buergel, “This Exhibition Is an Accusation: The Grammar of Display According to Lina Bo Bardi” in Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, Issue 26 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011), pp. 51-57.

[19] Cathrine Veikos, “To Enter the Work: Ambient Art” in Journal of Architectural Education, Vol. 59, No. 4 (Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis, Ltd, 2006), pp. 71-80.

[20] Romullo Baratto, 2015, photograph, Equipe ArchDaily Brasil, São Paulo.

[21] Lew Parrela, 1967, photograph, Instituto Lina Bo e P. M. Bardi, São Paulo.

[22] “Lina Bo Bardi, Architect of the People,” Modern Minute, July 5, 2018, https://modernminute.net/2018/07/05/lina-bo-bardi-architect-of-the-people/.