Palmerston-Little Italy is long overdue for a name change. The neighbourhood lies in central Toronto, nested between Bloor Street West, Bathurst Street, College Street and Dovercourt Road (figure 1). These boundaries are defined by the City of Toronto based on Statistics Canada’s census tracts and additional considerations including population size (City of Toronto, 2022).

Figure 1: A Map of Palmerston-Little Italy (City of Toronto, 2016)

This neighbourhood has a rich history due to its location in central Toronto and has been host to a wide range of urban changes in its time, one of the most relevant being its immigration patterns. As the name suggests, it is best known for its ethnic enclave of Italian immigrants. This reputation is supported by ethnic packaging: a term coined by Hackworth and Rekers (2005) that is defined as “a saleable form of ethnicity” (p. 211). Since the 1980s, Palmerston-Little Italy has been marketed as Italian to attract business, even as Italian immigration slowed. Through an exploration of academic literature surrounding this issue and a study of the neighbourhood itself, this paper finds that the ethnic packaging in Palmerston-Little Italy was caused by urban neoliberalism and has resulted in gentrification. It does not accurately reflect the current ethnic enclaves and is negatively affecting their urban experience.

The first step in understanding this issue is to review the academic literature on ethnic packaging and the concepts surrounding it before considering how these concepts apply to Palmerston-Little Italy. The most relevant of these is urban neoliberalism, an economic policy that Ugo Rossi (2015), a prominent human geographer, defines as “based on the conventional free market ideas” with emphasis on “the entrepreneurialization of local government, the privatization of public services, and the commodification of urban space” (p. 846). Simply put, urban neoliberalism seeks to financialize and privatize the city wherever possible.

The effects of this policy in Moss Park are detailed by Roberts and Catungal (2017) in their article about Toronto’s More Moss Park project: a community center and park revitalization. They write that the project took social justice and neoliberalized it through a series of political moves, most notably the normalization of privatization and philanthropy, and conclude that this results in “a neoliberal good that is available only to communities that can find willing donors, thus exacerbating already uneven urban landscapes of injustice and investment” (p. 460). The article claims that the current processes could lead to gentrification that would harm the community, not aid it. Gentrification, as Slater (2004) defines it, is “the production of space for—and consumption by—a more affluent and very different incoming population” (p. 1145). The spaces that this concept produces would not benefit the residents of Moss Park, which is what Roberts and Catungal are concerned about.

These concepts relate to Palmerston-Little Italy because ethnic packaging is a result of urban neoliberalism. This phenomenon occurs when an ethnic enclave is manipulated through neoliberal processes until it becomes harmful and an agent of gentrification. An ethnic enclave is a group with a shared cultural identity that is a minority within the country that the group resides in. These enclaves often make it easier for immigrants to find their footing in a new place because there is an area of people who share their culture and can create some familiarity in an unfamiliar environment. In Toronto, this is seen in many places including the congregation of Italians in Palmerston-Little Italy. The Italian businesses in the area were a natural side effect of their ethnic enclave, but the financialization and marketing of an Italian identity turned these businesses into agents of gentrification, similar to the Moss Park community centre.

These warnings about gentrification are echoed in an essay that Checker (2011) wrote about environmental justice: a subset of social justice. The essay examines a park expansion project in the Harlem neighbourhood in New York City and finds that while the public meeting about the project appeared “politically neutral and consensus-based”, the planners were not truly open to feedback from the marginalized communities. Checker concludes that environmental justice has been appropriated to serve “profit-minded development” (p. 210), resulting in environmental gentrification. This appropriation is similar to previous examples because it takes a positive concept, like social justice in Moss Park and ethnic enclaves in Palmerston-Little Italy, and neoliberalizes it until it is warped into something harmful to the marginalized communities it was supposed to support.

Vale (2015) shares Checker’s environmental concerns in his article about resilient cities, which questions the current use of the term ‘resilience’. He writes that it is used too broadly, having become somewhat of a buzzword in recent years, but it still holds value and could be used as a tool to evaluate cities if it is clarified. Vale concludes that “the value of resilience for understanding cities depends on treating cities as socio-ecological systems that are not stable and must evolve” (p. 627) This raises the question of how to treat cities as evolving systems and yet ensure that these changes do not negatively affect marginalized communities. It is possible to use a resilience framework “to improve the living conditions in stressed and distressed urban areas” (p. 628), but it must be done with careful consideration to avoid warping it into an agent of gentrification, as has been done with previously mentioned terms in this paper.

The texts thus far have provided valuable insight into neoliberalism and gentrification in various urban centres, but Murdie and Texaira (2011) bring the issue closer to home with a study of Little Portugal: a neighbourhood just southwest of Palmerston-Little Italy. Their study focused on the impact of gentrification on ethnic neighbourhoods through interviews with Portuguese residents. These interviews showed that the residents had both positive and negative views of gentrification, but “almost all respondents agreed that gentrifiers are becoming the defining population in the neighbourhood” (p. 79). The study concluded that this gentrification interferes with the ethnic enclave’s future, as it “is likely to decrease in importance as an institutionally complete Portuguese enclave” (p. 79). These concerns can be extended to Palmerston-Little Italy, as it has also been affected by gentrification that has put the ethnic enclaves at risk.

The last academic text that this paper reviews is focused on ethnic packaging as a concept. Hackworth and Rekers (2005) studied four neighbourhoods in Toronto that have business improvement areas (BIAs) based on ethnic identity, including the Little Italy BIA which is based in Palmerston-Little Italy. They considered “whether or not the cultural identity put forth and reproduced by the business improvement area was in line with or in contrast to the current demography of the surrounding neighbourhoods” (p. 216). They concluded that while the ethnic packaging that these BIAs sold was not entirely misrepresentative of the culture it claimed, it was misaligned with the neighbourhood’s ethnic enclaves. Additionally, it was carefully cultivated towards bringing in a more affluent population and thus acted as an agent of gentrification within its community. This is important to realize because this aspect of urban change brings culture and economics together, which is key to studying the issue of gentrification. In the nearly twenty years since this paper was written, Palmerston-Little Italy has only continued along the path that the authors highlighted.

It is because of this path that Palmerston-Little Italy deserves to be studied through the lens of ethnic packaging and gentrification. Hacksworth and Rekers write that historically, this neighbourhood saw significant waves of Italian immigration in the early twentieth century, and Italian businesses soon followed. This continued until the Second World War when changing attitudes towards Italians meant they could move to the suburbs. They did so in droves, with movement accelerating in the 1970s. This shift was reflected in the local commercial identity. Fewer businesses identified with Italy and the ones that did were geared towards tourists: trendy restaurants instead of family bodegas.

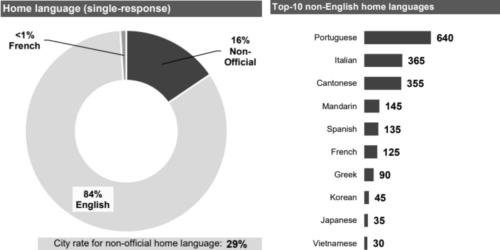

These shifts led to the current demographics. As immigration from Italy slowed and Italians moved out of the neighbourhood, Italians became a minority in the area (see figure 2). The neighbourhood’s 2016 profile highlights this reality and shows that non-official languages are a small percentage of home languages and within this category, Portuguese is more prevalent than Italian.

Figure 2: Italian Demographics by Home Language (City of Toronto, 2016)

These charts bring an important aspect of Palmerston-Little Italy to light: the Portuguese residents. Hacksworth and Rekers noted that “the neighbourhood is now more Portuguese, Chinese, and Vietnamese than Italian by almost any measure” (p. 212). This is still the case today well after Hacksworth and Reker published their study, but the commercial identity of the neighbourhood that the Little Italy BIA puts forward still does not reflect these residents. Ethnic businesses are a natural side effect of ethnic enclaves, which was seen in the Italian businesses of the early twentieth century, but a misaligned commercial identity can make it difficult to maintain ethnic businesses that are not included in the neighbourhood’s ethnic packaging.

This effect on business success can then impact livelihood, well-being, and general sense of belonging in the neighbourhood. Hacksworth and Reker write that the neighbourhood’s name was “one that irked some of the mostly, though not entirely, Portuguese-speaking population” (p. 211). It is entirely understandable that the Portuguese residents would be frustrated by the promotion of Italian identity when other ethnic enclaves are more prevalent than Italians but are not receiving the same attention. It seems that history is being prioritized over current reality. This is not to suggest that a choice must be made between one or the other, but it raises the question of where the balance between the two lies. The way the Little Italy BIA is functioning, as the name implies, is not representative of the totality of ethnic enclaves within the neighbourhood.

The Little Italy BIA has become the face of ethnic packaging in Palmerston-Little Italy. The BIA was founded in 1985, which was after many of the neighbourhood’s Italian community had already left for the suburbs. Its jurisdiction is focused on the businesses on College Street but its reputation extends far past this street. According to its website, “The board remains committed to creating a safe and vibrant place, while promoting the unique businesses and rich culture it is so well known for” (Little Italy BIA, 2022). However, one might question how much of this rich culture is an authentic byproduct of the community and how much has been curated so that wealthy city residents have somewhere to visit. This is because when this neighbourhood is discussed, it is these tourist geared restaurants and coffee shops that come to mind. It is true that the neighbourhood is historically Italian and that aspect should not be ignored, but the BIA markets it as currently Italian which is far less accurate.

A prime example of this marketing is the Taste of Little Italy festival. Every year the BIA puts on a three-day festival that closes College Street to vehicle traffic and turns it into an “opportunity to capture and explore the tastes and sounds of Italy and more right in the middle of Toronto as College Street transforms into a classic Italian piazza” (Little Italy BIA, 2022). There is a note at the end of the festival description about diverse food options, but this is the only hint that there are ethnic enclaves other than Italians in the area. This festival provides high levels of income for the businesses that are involved, but the concern with its distinctive Italian marketing is that the scales are weighted heavily towards Italian-themed businesses and others could struggle to keep up.

The Little Italy BIA, along with Toronto’s other BIAs, has a private-public partnership with the municipality. As discussed earlier, this is a concept that is championed by urban neoliberalism. Roberts and Catungal warned against the framing of these as necessary for community development when their use can result in gentrification if not applied carefully. The board of directors is made up of volunteers, and this philanthropy can make residents less critical of the decisions made by the BIA because their work is framed as a service. However, as urban residents, it is vital to consistently evaluate those in leadership positions and consider if they are working in the best interest of the people they represent.

In conclusion, this study of Palmerston-Little Italy contributes to an understanding of ethnic packaging because it highlights its origins in urban neoliberalism and its results of gentrification. These key course concepts are brought together through the lens of ethnicity: a perspective that is increasingly important in Toronto’s multicultural landscape. An interesting way that the research findings on the neighbourhood fit into the review of the academic literature is the Little Italy BIA’s beginning in the 1980s, which is the same time that urban neoliberalism began to take hold. This neighbourhood and some of the others studied are similar because they are examples of urban neoliberalism taking a positive concept and making it harmful by turning it into an agent of gentrification, which most affects marginalized communities. The Portuguese residents are the largest ethnic enclave in Palmerston-Little Italy, yet they are not reflected in the neighbourhood’s commercial identity which negatively impacts their ability to make a living and build a community in the city. However, this study of Palmerston-Little Italy differs from some of the literature because of its changing ethnic demographics that intersect with its economics: a unique aspect of urban change that has not been extensively researched.

This study of Palmerston-Little Italy relates to a key issue that has arisen in the course about how communities can develop and improve in a way that raises the entire community up and does not gentrify it, whether intentionally or not. It is the role of urban planners to navigate this as best they can. The research in this paper contributes further evidence to the importance of this role and the responsibility that urban planners have. Cities are evolving entities with rich histories, and Palmerston-Little Italy is a place where urban pasts and futures intersect. This provides a unique opportunity for urban planners to examine how ethnic packaging affects urban change, and perhaps find a more accurate name for this neighbourhood along the way.